You Don't Need Motivation. You Need to Kill What's Blocking You.

Most people think they lack motivation. The real problem? You’re burning energy fighting invisible friction. Here’s how to eliminate resistance and finally act.

You haven’t experienced anything near the action you’re capable of taking.

Many people think the gap between where they are and where they want to be is a motivation problem. They watch TED talks, like me, listen to podcasts about finding their “why,” and consume endless content about discipline and drive.

The reality is different. You have responsibilities. You have limited time. You have real constraints.

But you can transform your output without needing to “get motivated” at all.

You just need to understand what motivation is actually compensating for.

A pattern I’ve noticed in people who consistently execute: they don’t have more motivation than you. They don’t wake up more inspired. They don’t possess some magical reservoir of enthusiasm that you lack.

They’ve eliminated the invisible friction that makes starting feel impossible.

There are several ideas I want to share with you about resistance, action, and why everything you’ve been told about motivation is backwards.

This took me years to figure out. I couldn’t stay motivated no matter what I tried. I read book after book about motivation. Nothing worked. Maybe 1 out of 20 tips actually helped.

The tips below worked for me, and who knows, maybe they might work for you too.

Why Motivation Feels Necessary (But Isn’t)

“The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

Marcus Aurelius

Your brain is an energy management system optimized for survival.

Every action you consider taking gets filtered through a cost-benefit analysis that happens faster than conscious thought. Your brain calculates: How much energy will this require? What’s the guaranteed outcome? What’s the risk?

Your brain performs constant cost-benefit analyses faster than conscious thought

That should terrify you. It's terrifies me.

Because here’s what that means: your brain is actively looking for reasons NOT to act. It’s searching for uncertainty, difficulty, complexity, and using those signals to justify inaction.

This isn’t a bug. It’s a feature.

For 200,000 years of human evolution, conserving energy kept us alive. Unnecessary movement meant wasted calories. Uncertain outcomes meant potential death. Your ancestors who hesitated before running into the dark forest survived to pass on their genes.

You inherited a brain designed to avoid action unless absolutely necessary.

Think about the last time you needed to start something important. A work project. A difficult conversation. A lifestyle change.

Your mind generated a list:

Maybe I should research the best approach first

I’m not in the right headspace right now

I should wait until I have more time to do it properly

Let me just handle these smaller things first

I need to be more prepared before I begin

I…. add any of your excuses.

That’s not you being lazy.

That’s 200,000 years of evolutionary programming running its optimization protocol.

The problem is that modern life requires the opposite of what kept your ancestors alive. Success today demands action in the face of uncertainty. Progress requires starting before you feel ready. Achievement means moving when the outcome isn’t guaranteed.

Your brain experiences this as a threat.

So it does what it’s designed to do: it generates resistance. Doubt. Hesitation. A vague sense of “not yet.”

And here’s the trap: motivation is what you use to overpower that resistance.

You aren’t failing to act because you lack motivation.

You’re burning motivation just to overcome the invisible barriers your brain has constructed.

The Three Types of Resistance

Before we can eliminate resistance, we need to understand what we’re actually fighting.

Most people experience resistance as a single, monolithic force. That vague sense of “I don’t want to do this right now.”

But resistance has structure. It has components. And each component requires a different solution.

Activation Energy Resistance

This is the gap between intention and initiation. The moment where you know you should start, but you’re stuck scrolling, reorganizing your desk, or suddenly remembering seventeen other tasks that feel urgent.

Physics has a term for this: activation energy. The minimum energy required to start a chemical reaction.

Your brain treats every new action as a reaction that needs sufficient energy to begin. The more complex the task appears, the higher the activation energy required.

Psychological Reactance

This is your brain’s allergic reaction to feeling controlled. Even when you’re the one creating the expectation, even when you genuinely want the outcome, part of your mind rebels against the obligation.

You’ve experienced this: the project you were excited about on Friday suddenly feels oppressive on Monday morning. The commitment you made with enthusiasm now feels like a constraint.

Your brain is protecting your sense of autonomy by making you resist your own decisions.

Uncertainty Paralysis

This is what happens when your brain can’t predict the outcome clearly enough. You have twelve possible approaches. You’re not sure which is correct. You don’t know if you have the skills required. You can’t visualize the end state.

So your brain selects the safest option.

Which is nothing.

But here’s what most productivity advice gets wrong: it tells you to overcome these forces with willpower, discipline, and yes, motivation.

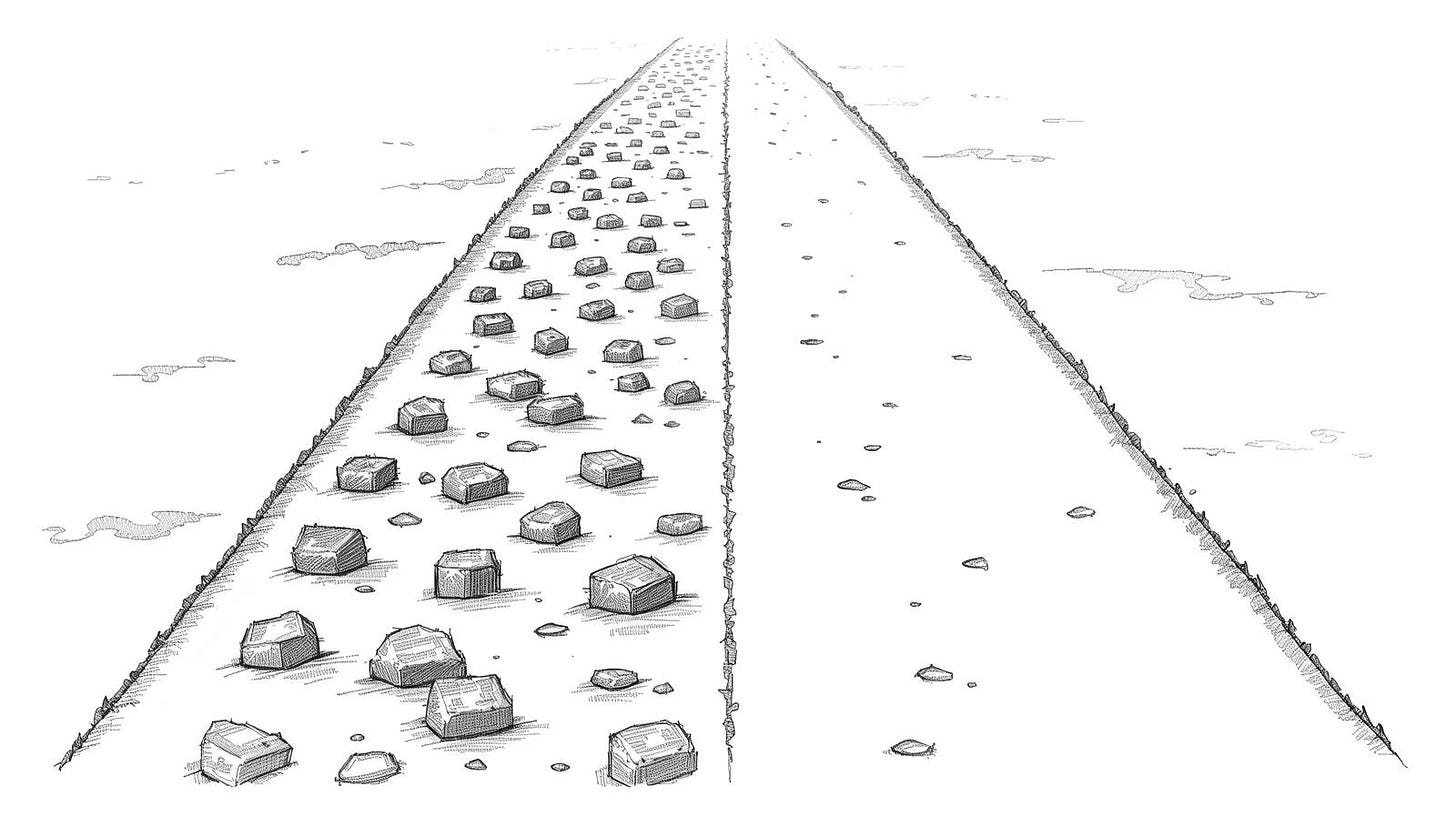

That’s like trying to drive a car with the parking brake engaged. Sure, if you press the accelerator hard enough, you might move forward. But you’re burning fuel fighting friction that shouldn’t exist.

So what’s missing?

The answer lies in the fact that you don’t need more force.

You need to remove the brake.

What I Learned Studying Professional Writers

I’ve always had some form of aversion toward hustle culture’s obsession with motivation.

The Instagram quotes. The morning routine videos. The productivity gurus promising that if you just find your “why” deeply enough, action becomes effortless.

It wasn’t until I started studying how professional creators/writers actually work that I understood why this advice never worked for me.

Ernest Hemingway wrote every morning, whether he felt inspired or not. He stopped mid-sentence so starting the next day required minimal activation energy.

Haruki Murakami runs before writing, using physical routine to bypass his brain’s negotiation phase entirely.

Steven Pressfield calls resistance “the most toxic force on the planet” and treats showing up to his desk like a soldier reporting for duty, regardless of how he feels.

These aren’t people with superhuman motivation.

They’re people who’ve systematically eliminated the need for it.

Here’s what I discovered when I reverse engineered their approaches: they don’t fight resistance. They don’t try to overpower it with inspiration or willpower.

They’ve built systems that make resistance irrelevant.

Hemingway’s mid-sentence stop? That’s activation energy reduction. He’s not starting from zero each morning. He’s completing a sentence, which requires almost no energy.

Murakami’s physical routine? That’s psychological reactance management. He’s not making a decision about whether to write. He’s executing a sequence that includes writing.

Pressfield’s militaristic approach? That’s uncertainty elimination. There’s no question about IF he writes or WHEN he writes. Those decisions don’t exist.

The secret they share: they’ve identified their specific resistance patterns and built countermeasures.

Not motivation. Not discipline. Not inspiration.

Strategic friction removal.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: the reason you haven’t done this is because it requires honest self-diagnosis. It’s easier to watch a motivation video and feel temporarily energized than to map the exact psychological mechanisms preventing you from starting.

But that temporary energy is expensive.

It’s finite. It depletes. And every time you burn it to overcome resistance, you’re training your brain that action requires massive force.

With that, the best approach to consistent action does not come from finding better reasons to start.

It comes from removing the reasons not to.

I used to think I just lacked discipline. Turns out I was just making everything harder than it needed to be.

What’s Actually Happening in Your Brain

There are a few moments in my life that I remember vividly.

One was sitting in my car in a parking lot, needing to make a phone call I’d been avoiding for three weeks. The call would take five minutes. I had the person’s number. I knew exactly what to say.

But I sat there for forty minutes, cycling through elaborate justifications for “not right now.”

That experience taught me something: resistance isn’t rational. It’s neurological.

The Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex

Your brain has a region called the anterior mid-cingulate cortex (aMCC). Think of it as your brain’s “difficulty sensor.”

It activates when you face challenges, make difficult decisions, or push through discomfort. Research suggests this region may show structural changes in people who regularly do hard things

This region of our brain doesn’t distinguish between physical difficulty and psychological resistance. To your aMCC, the activation energy required to start a difficult email feels identical to the effort of climbing stairs.

Most people experience resistance and interpret it as: “This task is too hard right now. I need to be more prepared.”

But that sensation isn’t proportional to actual difficulty.

It’s proportional to perceived friction.

The Dopamine Prediction Error

Your brain runs on a neurotransmitter called dopamine, which most people misunderstand completely. They think it’s about pleasure or reward.

It’s not.

Dopamine is about prediction. Your brain releases it when reality exceeds expectation. When you expect nothing and get something. When you predict difficulty and experience ease.

Every time you scroll social media instead of starting your task, your brain gets a tiny dopamine hit.

Expected effort (zero) matched by actual effort (zero). Perfect prediction.

Every time you reorganize your desk instead of beginning your project, same thing. Low effort predicted, low effort experienced. Dopamine confirms your choice.

But when you finally force yourself to start the task you’ve been avoiding? Your brain predicted massive difficulty. And sometimes, once you begin, it’s not as bad as you thought.

Dopamine should flood your system, right?

Except it doesn’t work that way when you’ve been avoiding something. Because you’ve trained your brain that THIS specific task requires enormous activation energy. The prediction error is too large. Your brain doesn’t trust it.

The Salience Network Hijacking

Your brain has a network called the salience network that determines what deserves your attention. It’s supposed to highlight important, relevant information and filter out noise.

But here’s what happens: every time you avoid a task, your salience network marks it as threatening. Not important. Threatening.

The next time you consider starting it, your network triggers the same neural pattern as encountering a predator. Your attention gets hijacked. You suddenly notice everything else that seems more urgent, more safe, more immediately rewarding.

You’re not weak, you’re not undisciplined. Your brain has been trained to perceive your most important work as a threat.

And motivation is the emergency override system you’re using to temporarily shut down that threat response.

What I learned over the years is that you can retrain these systems. Not through willpower. Through systematic resistance reduction.

The Friction Elimination Protocol

You need a system.

Not a motivation ritual. Not a morning routine. Not a productivity hack. They never worked for me.

A diagnostic and elimination protocol for the specific resistance patterns sabotaging your action.

I start every meaningful project by identifying friction points before they become obstacles. Most people wait until they’re stuck, then wonder why they can’t push through.

Step 1: The Resistance Mapping Exercise

Become brutally aware of three things:

What are you avoiding right now? List every task, project, or action you know you should take but haven’t. Be specific. “Work on business” is useless. “Write the first draft of the client proposal” is useful.

What story are you telling yourself about why? For each avoided task, write the exact thought you have when you consider starting it. “I need to be more prepared.” “I don’t have enough time to do it properly.” “I should wait until I’m less tired.”

What would make it stupid-easy to start? For each task, identify the smallest possible first action. Not the full task. Just the entry point. “Open the document” not “Write the proposal.”

Keep in mind that you’re not analyzing tasks. You’re analyzing your psychological response to tasks.

The task itself might be objectively simple. But if your brain has marked it as high-friction, it doesn’t matter.

Include the “anti-resistance” exercise: Write out every single reason your brain generates for not starting. Every excuse. Every justification.

Every “not yet.” Get them on paper where you can see them as the patterns they are, not the truths they pretend to be.

Step 2: The Activation Energy Audit

Your brain treats decision-making as effort. Every choice about how to start, when to start, or what to do first burns cognitive energy before you’ve done actual work.

The solution: eliminate decisions before you need to make them.

For your highest-friction tasks, create a pre-decision protocol:

Exactly when you’ll start (time-based trigger, not feeling-based)

Exactly where you’ll work (same place every time removes spatial decision)

Exactly what the first action is (open laptop, open document, write one sentence)

Exactly how long the minimum session lasts (15 minutes works, “until it’s done” doesn’t)

This isn’t about discipline. It’s about removing the micro-decisions that give your brain opportunities to negotiate.

Step 3: The Certainty Builder

Your brain resists uncertainty more than difficulty. If you’re stuck, it’s often because you don’t know what “done” looks like.

The best way to eliminate uncertainty paralysis is to define completion before you start.

For every avoided task:

What does “finished” look like specifically? (Not “better” or “good enough”, actual completion criteria)

What’s the absolute minimum that counts? (The floor, not the ceiling)

What information do you actually need vs. what you’re using research as procrastination?

Then start with the minimum. Not because you’re aiming low. Because your brain needs proof that completion is possible.

Once you finish the minimum, you’ll have momentum. Once you have momentum, your brain recalculates the effort prediction. Once the prediction drops, resistance drops.

The minimum isn’t the goal. It’s the mechanism for bypassing your brain’s threat response.

Step 4: The Environment Forcing Function

Every environment you’re in is either reducing friction or creating it. Your phone is nearby. Your desk is cluttered with twelve half-finished projects. Your comfortable chair invites distraction.

If your environment requires willpower to stay focused, you’re going to lose that battle eventually.

Environmental design should make the right action easier than the wrong action.

For deep work:

Phone in different room (not just silent, physically separated)

Single project visible (everything else closed or out of sight)

Uncomfortable enough that you want to finish and leave (not punishing, but not luxurious)

Note: Giving up my phone was hard for me and sometimes it’s still is, so I bought myself a plastic box with a timer. I’d lock my phone inside, set it for an hour, and have to wait out the full hour to get it back. It was the only way I could limit the constant checking.

For avoided tasks:

Pre-open the exact file/tool/document you need

Close every other application

Set a timer for the minimum session you defined

That is the only piece of productivity advice you need: make starting require less effort than avoiding.

Our anti-resistance frame is composed of:

Mapped psychological patterns (you know what you’re fighting)

Eliminated decisions (no negotiation opportunities)

Defined completion (no uncertainty paralysis)

Engineered environment (friction works for you, not against you)

This creates a tight feedback loop that encourages your brain to recalculate effort predictions, which reduces activation energy, which makes starting easier, which proves to your brain that resistance was disproportionate.

That’s the foundation. That’s what eliminates the need for motivation.

Why Resistance is Actually Information

You’re supposed to feel hesitation before starting something important.

You’re supposed to experience doubt when facing uncertainty.

You’re supposed to notice the gap between where you are and where you’re trying to go.

The problem isn’t that you feel resistance. The problem is that you’ve been taught to interpret resistance as evidence that you’re not ready, not capable, or not motivated enough.

What in the world did you expect to happen when you decided to do something that actually matters to you?

Did you think your brain, optimized for 200,000 years to conserve energy and avoid uncertainty, would just cooperate? That you’d wake up inspired every day, resistance-free, flowing effortlessly toward your goals?

The most successful people don’t flinch at resistance.

They expect it. They recognize it as confirmation they’re attempting something difficult enough to be worthwhile.

There are levels to how you engage with action:

Level 1 is waiting until you feel motivated. Letting your emotional state determine your behavior. This guarantees inconsistency because emotions are variable by design.

Level 2 is using discipline to override motivation. Forcing yourself to act despite not feeling like it. This works, but it’s energetically expensive. You’re spending willpower to fight your own resistance.

Level 3 is removing the need for both motivation and discipline by eliminating the resistance that made them necessary.

Many people are stuck between Level 1 and Level 2, burning enormous energy trying to become more disciplined, more motivated, more consistent.

They never consider that the game is removing friction, not increasing force.

Think of your brain like a self-driving car learning to navigate. For months, maybe years, it has received input that certain tasks require massive effort. Every time you’ve hesitated, procrastinated, or needed motivation to start, you’ve reinforced that pattern.

But patterns can be retrained.

Every time you start despite resistance and discover it wasn’t as bad as predicted, you’re updating the model. Every time you reduce activation energy and make starting easier, you’re teaching your brain a new pattern.

Eventually, the tasks that once required motivation become automatic. Not because you’ve become more disciplined, but because your brain has recalculated the effort required and stopped generating resistance.

I wish I could tell you that everyone reading this can eliminate all resistance immediately.

But if that were the case, the ability to act consistently would lose all meaning.

You must go through the process of mapping your resistance, eliminating your friction, and proving to your brain that action doesn’t require the force it’s been predicting.

The difference between people who act and people who wait for motivation isn’t internal strength.

It’s systematic friction removal.

And you already have everything you need to begin.

I still catch myself sometimes, sitting at my desk at work or home, feeling that old familiar weight. The sense that I need to be “ready” before I start. That I should wait until I feel different.

Then I remember that I’m not waiting for a feeling. I’m looking for friction I haven’t removed yet.

Articles you shouldn’t miss: