When Every Message is Perfect, No Message Matters

AI made personalization free. Now every inbox feels fake. A deep look at automated outreach, voice cloning, and why trust online is quietly collapsing.

A few months ago, my friend, Jana, showed me her LinkedIn inbox. We were sitting in a coffee shop near Wenceslas Square (if you are not from the Czech Republic, it's located in Prague), it was raining, and she’d just finished complaining about the espresso being too bitter. She scrolled through maybe thirty messages. Every single one referenced her recent post about candidate ghosting. Everyone used her first name and company name as well.

Several mentioned specific details from her profile, her company’s recent investment, and the fact that she’d spoken at a conference two weeks earlier.

Every single one of them was trying to pitch their recruitment agency services with a hyper-personalized email.

“Five years ago, this would’ve meant something,” she said.

Now she deletes them in batches without reading past the first line. Because she knows. They all know the messages are good, too good, and far too many. Written by tools that can scrape a profile, analyze posting patterns, and generate something that sounds like it came from a human who actually read her work and thought about it for ten minutes.

The crazy part isn’t that the messages are obvious spam. It’s that most of them aren’t, and they all pass her company and Gmail filters without any problems.

Inbox looked normal until it wasn’t

The shift happened sometime in late 2024, though nobody I’ve talked to can pin down an exact month. Messages started getting better. Not in the “Hey {FirstName}, I noticed your company” obvious mail-merge way we knew for years, but they actually got better. They referenced specific posts, used natural language, made relevant observations, and included details that suggested the sender had spent real time on research.

Jana said the first few felt flattering. Someone at a vendor company sent her a message about a talk she’d given, mentioned a specific framework she’d used, asked a thoughtful follow-up question. She responded to those messages, as she thought a human had written them. They even had a decent exchange.

Then she noticed the same person had sent near-identical “personalized” messages to six other recruiters she knew. Same structure, different details swapped in. It was a Tuesday afternoon, she remembers that because she had a candidate interview at 3pm that she almost missed because she was too annoyed by the realization.

The email volume accelerated. Ten personalized messages a week became thirty. Then fifty, often sent not only to her company email but also to her LinkedIn, and then her WhatsApp started getting them too. All thanks to AI and multichannel outreach. If there is one thing I personally do not like, it is this.

She started getting text messages even on her personal phone number, which she’s pretty careful not to share publicly. Each one had enough context to feel legitimate. Not all of them were selling something obvious. Some were just... conversations. Networking attempts, people “reaching out” because they’d “been following her work.”

She stopped responding to anything that felt too smooth. If a message had zero typos, perfect grammar, and hit every psychological trigger in the relationship-building playbook, it went to trash.

The irony is that now she probably deletes real messages from real people who just happen to write well. But the math doesn’t work anymore. When responding to one message costs five to ten minutes (if you are not using AI), and the hit rate on genuine humans is maybe one in twenty, you stop playing.

The economics of fake intimacy

Personalization used to be expensive. Writing a good cold email meant research, time, and having the right skills. You had to read someone’s work, understand their context, find a genuine connection point. That took time. And as we know, time is money. So personalization was reserved for high-value targets. When you got a truly personalized message, it meant something because it meant someone had invested scarce resources in reaching you specifically.

AI makes that investment free. Or close enough to free that it rounds to zero. You can now generate a hundred personalized messages in the time it used to take to write one. Each message can reference specific details, mirror communication styles, adapt to the recipient’s industry, and do it all without human intervention past the initial setup.

There’s interesting research on this, though not specifically about AI-generated outreach. Paul Rozin at Penn studied something he called “contagion” in the 1980s, looking at how people value objects. A sweater worn by a celebrity is worth more than an identical unworn one. But if you tell someone the celebrity sweater was duplicated perfectly, the value collapses. Not because the quality changed. Because scarcity did.

The same mechanism breaks personalization. When everyone can generate messages that look hand-crafted, the hand-crafting loses value. The signal degrades. A thoughtful email used to mean “this person cares enough about reaching me to invest twenty minutes of focused effort.” Now it means “this person has access to ChatGPT and a LinkedIn scraper.”

The flood is already here in sales and recruiting. It’s coming for every other channel. Fundraising, political campaigns, and especially in scams. It's even coming for personal communication between people who actually know each other, because why wouldn’t you use AI to help craft a better apology, a clearer explanation, a more thoughtful thank-you note?

I’m not sure where the line is between “using a tool to communicate better” and “automating communication to the point where it stops being yours.” I suspect that line is fuzzier than we want it to be, and I also suspect we’re going to cross it repeatedly without noticing until the damage compounds.

It feels a bit weird when someone reaches out on LinkedIn saying they admire your work, but you can tell they haven’t even visited your profile, and the message is AI-generated, thanks to LinkedIn AI. And what do you do? You reply with a message also generated by AI, or at least use AI to fix the grammar.

Throughout this whole process, the human part was pretty small. All we had to do was click “generate” to create the content and then “send” to share it.

Spoofed voices and cloned faces aren’t edge cases anymore

My friend Petr’s mother called him two months ago. She was crying. She said she needed money immediately; there'd been an accident, she couldn't explain on the phone, and asked him to send 2,000 euros to this account number right now. He was about to do it, because the voice was perfect; he told me that the crying sounded real.

He called her back on the same number to confirm the account. She answered that she was fine, just watching television at home. Had no idea what he was talking about. Someone had cloned her voice, probably from a video she’d posted to Facebook a few years ago.

This isn’t theoretical anymore. Voice cloning tools are widely available; ElevenLabs and many others can do that within minutes, sometimes in seconds. Video deepfakes are getting harder to spot. The technology to spoof a video call exists and is getting cheaper every month. I read about a case in Hong Kong where a finance worker transferred $25 million after a deepfaked video conference call with people who looked exactly like the company’s CFO and other executives. That was February 2024; if you check new versions of Kling or Seedance, these tools are way better now.

What happens when the base assumption shifts from “if I hear someone’s voice, it’s probably them” to “I can’t trust audio or video without secondary verification”? We don’t have cultural norms for that yet. We’re still operating on pre-AI threat models where sophisticated attacks were rare enough to be newsworthy.

A professor of Psychology at Rider University, John Suler, identified six factors that make people behave differently online versus in person. Anonymity was one, but so were invisibility, asynchronicity, and what he called “dissociative imagination1,” the sense that online interactions aren’t quite real. That was 2004. Now add perfect voice mimicry, video that looks real, and AI that can hold a conversation in real-time with almost no latency, while pretending to be someone you trust.

The question isn’t whether this will be used maliciously. It already is, but the question is how fast the cultural immune system adapts. I often wonder, if its even possible.

What makes something feel real when everything can be simulated

We rely on dozens of small signals to determine authenticity: voice timbre, word choice, and response latency. The way someone structures an explanation, typos in predictable places, even though AI is now able to fix any text. References to shared context that would be hard for an outsider to fake.

All of those signals can be mimicked now. Not perfectly, not yet, but well enough to fool most people most of the time. And the error rate drops every few months. Just take Instagram or TikTok videos, a few months ago you would spot an AI video immediately, now you wonder, is that person real or another AI?

When authenticity can be faked perfectly, trust shifts from content to metadata. Not what someone says, but how they say it and through what verified channel. We’re already seeing this with two-factor authentication, blue checkmarks, verified badges. But those systems break too. Verification becomes a new attack surface.

There’s probably a version of this where decentralized identity systems solve the problem. Cryptographic signatures, web of trust models. But I’m quite skeptical about these things. Not because the technology can’t work, but because adoption requires changing behavior for billions of people, and the threat model is invisible until it personally affects you. Most people won’t implement security measures until after they’ve been burned. By then the damage is done.

I am always shocked by how many people do not even have 2FA for their emails, unless their email provider forces them to use it.

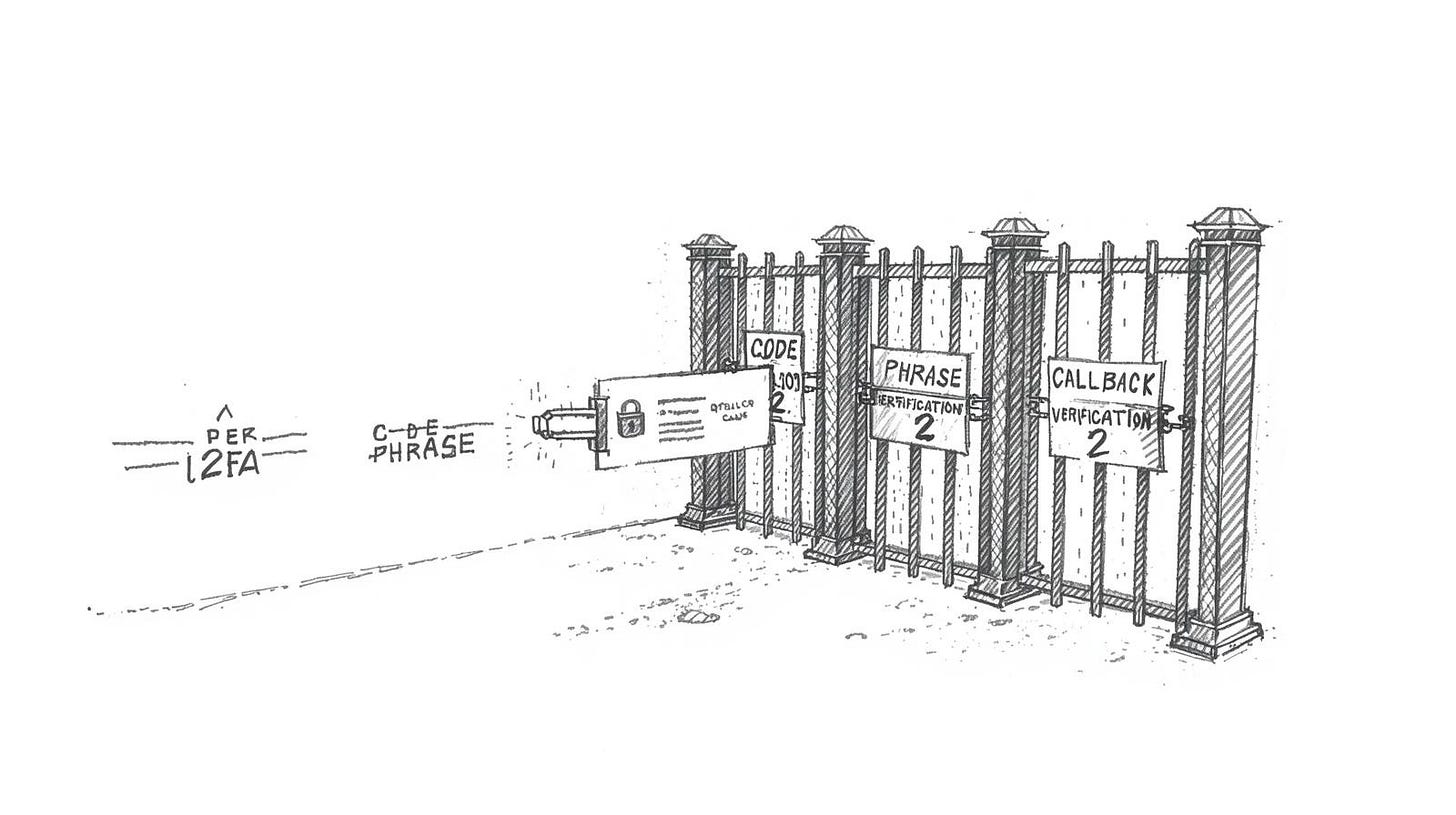

Safe words, verification codes, and…

I’ve started hearing about families creating verbal passwords. My friend Alice, who lives in London, told me that her parents decided on a code phrase after reading about voice-cloning scams. If anyone in the family calls asking for money or claiming there’s an emergency, they have to use the phrase first. She said it feels paranoid and also completely reasonable, which is a weird combination.

Companies are testing similar systems. Some are implementing secondary verification for any request involving financial transfers, even if it comes from a known internal email address. Call back on a verified number, confirm via a different channel.

The cost is time and annoyance. Every verification step slows down legitimate communication. If you’re in a role where fast decisions matter, adding three verification layers to every high-stakes conversation could be the difference between closing a deal and losing it. But not adding those layers could be the difference between keeping your job and getting fired for falling for a scam that should’ve been obvious in retrospect. Perhaps I’m being overly cautious, but this is the reality we’re facing.

I don’t think we’ve figured out the right tradeoff yet. We’re still in the phase where most people don’t implement any protection because the threat feels abstract or something you are reading about on the internet.

That changes the first time someone they know gets hit. Then the pendulum swings too far in the other direction, everything gets locked down, and productivity craters. Eventually, we find some middle ground. But there’s a transition period that’s going to be messy.

The other problem is that authentication systems create exclusion. If you require cryptographic verification for all communication, you’ve just cut off anyone who doesn’t have the technical literacy to set that up. All my friends use WhatsApp, I am trying to avoid it as it's a plague, but getting them to Signal is almost impossible.

The security layer becomes a barrier to connection, especially for elderly relatives. Maybe that’s an acceptable tradeoff, I’m not sure.

Friction as a signal

There is something strange I keep noticing. The most credible messages I get now are the ones with mistakes. Not obvious spam mistakes, but human ones. Typos that autocorrect didn’t catch, sentences that wander. An apology for taking three days to respond because they got busy with something unrelated.

A client sent me a message last week that started with “Sorry, just saw this, my kid had a thing at school and then I forgot to check email until now.” That sounds real. AI doesn’t forget to check email. AI doesn’t have kids with school events. AI would generate a response within seconds or wait a calculated amount of time to simulate busyness, but it wouldn’t explain the delay with a specific mundane excuse that adds no strategic value to the message.

I realize this is temporary, eventually AI will learn to add strategic imperfection. You can do it now with the right prompting, but it still does not feel real, at least to me. The next generation of tools will insert deliberate typos in statistically appropriate places. Add random delays, generate plausible excuses for slow responses. But we’re not there yet (at least I don't think we are), and in the gap between now and then, sloppiness becomes a weak signal of authenticity.

The long-term equilibrium probably isn’t “imperfection equals authenticity.” That’s too easy to game. More likely we end up in an arms race between authentication and spoofing, with verification costs rising over time until most communication happens through gated channels that require some form of identity proof.

Email becomes unusable, direct messages become unusable. Maybe we all retreat to small, verified networks where everyone knows everyone else and strangers can’t get in without a referral, something like Facebook or LinkedIn, but for people we really know.

That has costs too, network effects matter. Open communication enabled a lot of valuable things. Weak ties connect disparate communities. Serendipitous connections happen because someone you don’t know can reach you. Close all that down and you lose something real.

I don’t have a clean answer here. The flood is already happening and it’s going to get worse. Most of the proposed solutions either don’t scale or create new problems. We’ll probably muddle through with some combination of verification systems, behavioral adaptation, and resigned acceptance that a certain percentage of communication is now just noise you have to filter.

What I do know is that the thing I used to value about personalized outreach, the sense that someone had invested time in understanding who I was and what I cared about, doesn’t work anymore. The signal is degraded past the point where I can trust it. And I don’t think we’re going back to a world where personalization means scarcity. The tools exist, and people will use them.

Everything these days also feels like a numbers game. I still remember the time when recruiters spent time writing personalized emails, and now? It’s easy to reach 5,000 people in minutes; the only thing you need to do is hit one button and add as many recipients as you’d like.

Maybe five years from now we’ll have cultural norms that make this manageable. Maybe we’ll look back and laugh at how we used to trust email addresses and phone numbers as identity proof. Or maybe we’ll be stuck in an equilibrium where every conversation requires so much verification overhead that we only communicate with people we already know, and the cost of establishing trust with a stranger is prohibitively high.

I still check my messages. I still respond to some of them. But the bar keeps rising for what counts as credible enough to warrant attention, and I’m probably missing real opportunities because I can’t tell them apart from generated noise.

Articles you shouldn’t miss:

Dissociative imagination refers to a mental state where, through intense absorption, an individual detaches from their current surroundings to engage in vivid, immersive fantasies or alternate realities.